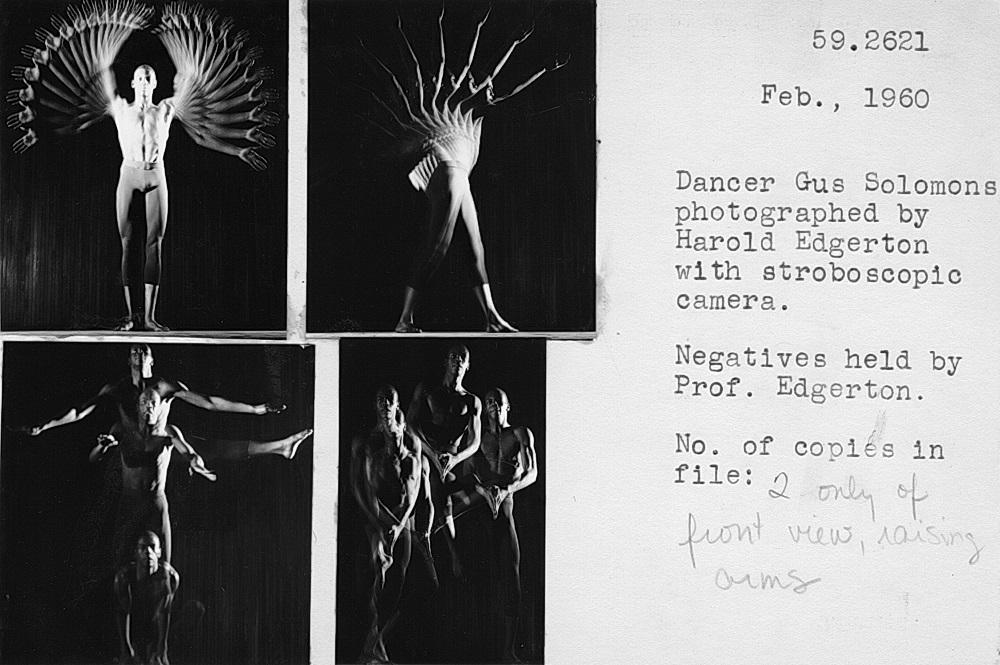

Catalog card: Gus Solomons and Harold Edgerton, 1960

MIT Museum catalog depicts dancer and architecture student Gus Solomons '61 photographed by electrical engineering professor Harold Edgerton with stroboscopic camera, February 1960.

Gus Solomons

Gustave M. Solomons, Jr. '61 holds a BA in Architecture (1961) from MIT. He began dance lessons while attending MIT, and his first teacher was E. Virginia Williams, founder of the Boston Ballet Company. Throughout his time at the Institute, he was very involved in Tech Show and Dramashop productions. Upon graduation from MIT, Solomons moved to New York City, where he worked to find new experimental forms of dance by deconstructing learned structures. Today Solomons is an accomplished dancer, choreographer, dance critic, and actor. He returned to MIT in September of 2002 as an MLK Visiting Scholar, hosted by Music and Theater Arts.

Solomons' younger brother Noel W. Solomons served as an Associate Professor of Clinical Nutrition at MIT from 1977 to 1984. Their father, Gus Solomons, Sr. '28, was an early MIT graduate.

As a member of MIT’s faculty, [Harold] Edgerton continued to make photographic studies, often with dramatic flair as evidenced by his attraction to speeding bullets, falling milk droplets, and hummingbirds stilled in flight. Capturing what was outside the capacity of the human eye endlessly engaged him and surprised others.

In 1960, Edgerton became interested in recording the human body in dance. For this, he recruited the young MIT student Gus Solomons as his subject. The dancer, later a noted performer, believed in the uniqueness of his own movement, which he felt Edgerton’s studies would prove. The results of these sessions are among the most poetic Edgerton made. Here, the moving arms of the lithe and strong Solomons are recorded as wing-like trails.

Harold Edgerton

From MIT Museum exhibit, Flashes of Inspiration: The Work of Harold Edgerton

Harold “Doc” Edgerton (1903–1990) began his graduate studies at MIT in 1926. He became a professor of electrical engineering at MIT in 1934. In 1966, he was named Institute Professor, MIT's highest honor.

With his development of the electronic stroboscope, Edgerton set into motion a lifelong course of innovation centered on a single idea—making the invisible visible. An inveterate problem-solver, Edgerton succeeded in photographing phenomena that were too bright or too dim or moved too quickly or too slowly to be captured with traditional photography.

In the early days of his career, Edgerton's subjects were motors, running water and drops splashing, bats and hummingbirds in flight, golfers and footballers in motion, his children at play. By the time of his death at the age of 86, Edgerton had developed dozens of practical applications for stroboscopy, some that would influence the course of history.

The strides that Edgerton made in night aerial photography during World War II were instrumental to the success of the Normandy invasion and, for his contribution to the war effort, Doc was awarded the Medal of Freedom. During the Cold War, Edgerton and his partners at EG&G (Edgerton, Germeshausen, and Grier) made it possible to document nuclear explosions, an advance of incalculable scientific significance. In the last three decades of his life, Edgerton concentrated on sonar and underwater photography, illuminating the depths of the ocean for undersea explorers such as Jacques Cousteau, who dubbed his good friend “Papa Flash.”

Doc's genius for revealing slices of time to the naked eye also engaged the public imagination. In part, this had to do with his astute choice of subject matter: Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, the acrobats of the Moscow Circus, British tennis star Gussie Moran. But Doc's most famous study—and possibly his favorite—the milk-drop coronet, transcended its simple subject. The image, formed by the splash of a drop of milk, not only introduced the poetry of physics into popular culture, but forever altered the visual vocabulary of photography and science.