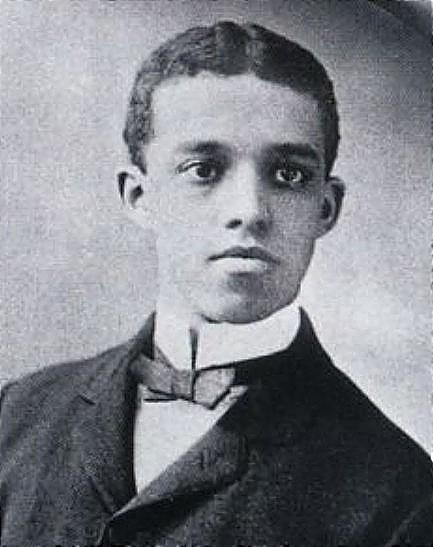

Frederick J. Hemmings, 1897

Frederick John Hemmings '97 of Roxbury in Boston, Massachusetts was the son of Robert W. Hemmings, a “coachman” and “janitor,” and homemaker Dora L. Hemmings, both originally from Virginia. There were three other siblings: Anita, Robert Jr. and Elizabeth.

Racial Identity

Both parents identified as “mulattoes”. In fact, Robert Hemmings is believed to be a distant family relation of Sarah “Sally” Hemings, a mixed race woman enslaved under Thomas Jefferson. (Historians believe Jefferson fathered six of her children. This claim was made public during his first term as president and has since remained the “Hemings-Jefferson Controversy”.)

The Hemmings’ family lived in Roxbury, a historically black part Boston. Despite lacking means, the parents wanted the best education for their children. In 1893, they sent both their daughter and their son to study at top schools: Anita went to Vassar and the younger Frederick to MIT. How each sibling negotiated racial identity at their respective schools reflects issues of race, gender, class, and institutional culture of the time. Anita passed for white at Vassar; Frederick is identified as “colored” in his student records at MIT.

Frederick had always been more cautious than his sister when it came to interacting with and befriending those outside the Negro community. His slightly darker skin, the fact that he had never passed as white for more than a few days, his reality of being a Negro student in a white world, and his naturally circumspect character meant he never dared take the risks his sister did.

The Gilded Years: A Novel by Karin Tanabe (Washington Square Press, 2016)

Frederick’s sister Anita F. Hemmings dreamed of attending Vassar College, one of the most elite women colleges in the country. With little to no chance that Vassar would accept a black student, Anita and her parents decided she pass for white, identifying as French and English on her application. Once admitted, Anita proved to be an excellent student who fully participated in Vassar’s social and academic life.

There is speculation that a visit by her darker-skinned brother Frederick from MIT fueled suspicions about Anita’s olive skin. The ensuing revelation of Anita’s ancestry caused a media scandal that consumed Vassar and society circles, threatening her chances of graduating. She nevertheless became the first black student to graduate from Vassar College in 1897, the same year her brother Frederick graduated from MIT.

At the Institute

Hemmings graduated from English High School in Boston and sat the MIT entrance exam, passing all subjects except arithmetic, which he made up shortly after entering MIT in 1893. He was admitted as a regular student in Chemistry (Course V). His academic record at MIT was generally excellent, showing honors, credits, and passes in most subjects. The only exception occurred during his junior year, when he failed three subjects. This was near the time Hemmings made a visit to his sister, whose passing for white at Vassar seemed to be a constant source of concern for him and his parents. It is quite possible that the impact of the scandal on the Hemmings family also had an adverse effect on Frederick’s grades.

During his final two years at MIT, however, Hemmings's academic efforts and performance were recognized in two scholarships that he was awarded during his final two years at MIT. His final thesis was entitled "The Change that Glucose Undergoes During Fermentation."

Post-MIT

After MIT, Hemmings worked as a chemist with Henry Carmichael, Analytical and Consulting Chemist in Boston. Around 1911, he left to accept a position as assistant chemist at the U.S. Navy Yard in Charlestown, MA. He was promoted to associate chemist or chemist by 1926 and to chief chemist by 1944, retiring before 1948.